Testing

If you are using Apache Causeway to develop complex business-critical applications, then being able to write automated tests for those applications is massively important. As such Apache Causeway treats the topic of testing very seriously.

This guide describes those features available to you for testing your Apache Causeway application.

Unit tests vs Integ tests

We divide automated tests into two broad categories:

-

unit tests exercise a single unit (usually a method) of a domain object, in isolation.

Dependencies of that object are mocked out. These are written by a developer and for a developer; they are to ensure that a particular "cog in the machine" works correctly

-

integration tests exercise the application as a whole, usually focusing on one particular business operation (action).

These are tests that represent the acceptance criteria of some business story; their intent should make sense to the domain expert (even if the domain expert is "non-technical")

For larger "modular monoliths", integration tests can also run against a particular vertical slice of the application. The SimpleApp starter app demonstrates this technique.

To put it another way:

|

Integration tests ensure that you are building the right system Unit tests ensure that you are building the system right. |

Integration tests leverage Spring Boot’s integration testing infrastructure,in particular using @SpringBootTest. This configures and bootstraps the Apache Causeway runtime, usually running against an in-memory database.

Integ tests vs BDD Specs

We further sub-divide integration tests into:

-

those that are implemented in Java and JUnit (we call these simply "integration tests")

Even if a domain expert understands the intent of these tests, the actual implementation will probably be pretty opaque to them. Also, the only output from the tests is a (hopefully) green CI job

-

tests (or rather, specifications) that are implemented in a behaviour-driven design (BDD) language such as Cucumber. We call these "BDD specs", and provide the BDD spec support module to makes Cucumber and

@SpringBootTestwork together.The natural language specification then maps down onto some glue code that is used to drive the application. But the benefits of taking a BDD approach include the fact that your domain expert will be able to read the tests/specifications, and that when you run the specs, you also get documentation of the application’s behaviour ("living documentation").

It’s up to you whether you use BDD specs for your apps; it will depend on your development process and company culture. But if you don’t then you certainly should write integration tests: acceptance criteria for user stories should be automated!

Simulated UI (WrapperFactory)

When we talk about integration tests/specs here, we mean tests that exercise the domain object logic, through to the actual database. But we also want the tests to exercise the app from the users’s perspective, which means including the user interface.

For most other frameworks that would require having to test the application in a very heavy weight/fragile fashion using a tool such as Selenium, driving a web browser to navigate . In this regard though, Apache Causeway has a significant trick up its sleeve. Because Apache Causeway implements the naked objects pattern, it means that the UI is generated automatically from declared domain-objects, -views and -services. This therefore allows for other implementations of the UI.

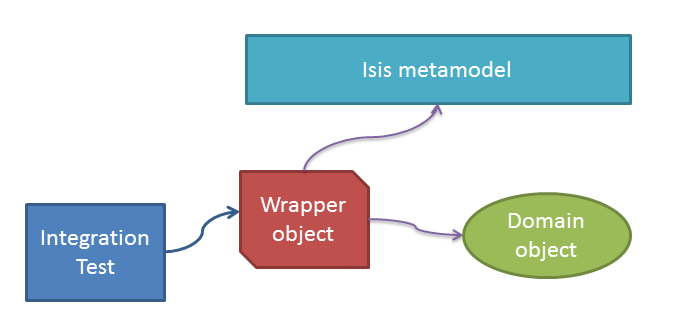

The WrapperFactory domain service allows a test to wrap domain objects and thus to interact with said objects "as if" through the UI:

If the test invokes an action that is disabled, then the wrapper will throw an appropriate exception. If the action is ok to invoke, it delegates through. There’s more discussion on the wrapper factory in the integ test support chapter.

What this means is that an Apache Causeway application can be tested end-to-end without having to deploy it onto a webserver; the whole app can be tested while running in-memory. Although integration tests re (necessarily) slower than unit tests, they are not any harder to write (in fact, in some respects they are easier).

Dependency Injection

Spring Boot will automatically inject dependencies into integration tests and services, and Apache Causeway extends this to also inject services into every domain object (entity or view model). This is most useful when writing unit tests; simply mock out the service and inject into the domain object.

There are a number of syntaxes supported, but the simplest is to use @jakarta.inject.Inject annotation; for example:

@jakarta.inject.Inject

CustomerRepository customers;Domain services are discovered by Spring Boot, either explicitly referenced in the @Import annotation, or picked up from class path scanning of @ComponentScan. Any service annotated or meta-annotated with @Component can be discovered; this includes classes annotated with Apache Causeway' @DomainService.

Given/When/Then

Whatever type of test/spec you are writing, we recommend you follow the given/when/then idiom:

-

given the system is in this state (preconditions)

-

when I poke it with a stick

-

then it looks like this (postconditions)

A good test should be 5 to 10 lines long; the test should be there to help you reason about the behaviour of the system. Certainly if the test becomes more than 20 lines it’ll be too difficult to understand.

The "when" part is usually a one-liner, and in the "then" part there will often be only two or three assertions that you want to make that the system has changed as it should.

For unit test the "given" part shouldn’t be too difficult either: just instantiate the class under test, wire in the appropriate mocks and set up the expectations. And if there are too many mock expectations to set up, then "listen to the tests" … they are telling you your design needs some work.

Where things get difficult though is the "given" for integration tests; which is the topic of the next section…

Fixture Management

In the previous section we discussed using given/when/then as a form of organizing tests, and why you should keep your tests small.

For integration tests though it can be difficult to keep the "given" short; there could be a lot of prerequisite data that needs to exist before you can actually exercise your system. Moreover, however we do set up that data, but we also want to do so in a way that is resilient to the system changing over time.

The solution that Apache Causeway provides is fixture scripts, supported by a domain service (also) called FixtureScripts. This defines a pattern (command pattern and composite pattern) with supporting classes to help ensure that the "data setup" for your tests are reusable and maintainable over time.

Fake data

Apache Causeway provides the Fake Data library to assist with this.

|

Using fake data works very well with fixture scripts; the fixture script can invoke the business action with sensible (fake/random) defaults, and only require that the essential information is passed into it by the test. |

Feature Toggles

Writing automated tests is just good development practice. Also good practice is developing on the mainline (main, trunk); so that your continuous integration system really is integrating all code.

Sometimes, though, a feature will take longer to implement than your iteration cycle. In such a case, how do you use continuous integration to keep everyone working on the mainline without revealing a half-implemented feature on your releases?

One option is to use feature toggles. These let us decouple deployment (meaning shipping code into production) from release (meaning let users have access to and use that feature).

At its simplest, a feature toggle could be a global variable disabling the functionality until fully ready, or it might even just be implemented using security. More sophisticated implementations make access more dynamic, for example by granting access to "alpha" or canary users.